It is a calm Saturday morning at Ngege village, in Korando, Kisumu West. Charles Opondo is clutching two bunches of bananas from his farm.

“Welcome home. You are right in time,” he murmurs to this writer as he rushes to the house and comes out with three plastic seats.

“Our compound is full of trees, and it is refreshing to sit under the shades,” he adds as we pick the chairs. Fresh breeze from the shores of the lake beneath makes it more aesthetic.

Opondo, 37, has been a farmer for the past five years after he quit fishing due to dwindling catch, and he is not looking back.

The compound is populated with fruit trees, such as mangoes, oranges, and avocados, as well as bananas, pawpaw, cassavas, and many other food crops.

After high school in the early 2000s, Opondo moved to Nairobi where he trained as a tailor, and worked for 15 years. But this was not satisfying.

“Every time I came home to visit, I would see my relatives and friends doing well; some having built good houses, while others were putting up investments, but I was barely surviving in Nairobi,” said Opondo.

Opondo told Lake Region Bulletin that it was then that he relocated from Nairobi, back to his Ngege home, where he joined his peers in fishing, and sand harvesting.

But it did not take long before the harsh reality dawned on him. The fish stocks in the lake was fast reducing, and fishermen could barely manage to get enough.

Fishing pressure on Lake Victoria

According to Kenya Marine and Fisheries Institute (KMFRI), unregulated human activities and climate change remain the biggest threats to the lake’s ecosystem.

There is fishing pressure, water quality changes, unbalanced predator-prey relationship, and governance issues which have to be checked

Dr Christopher Aura, the Director of Fresh Water Systems Research at KMFRI

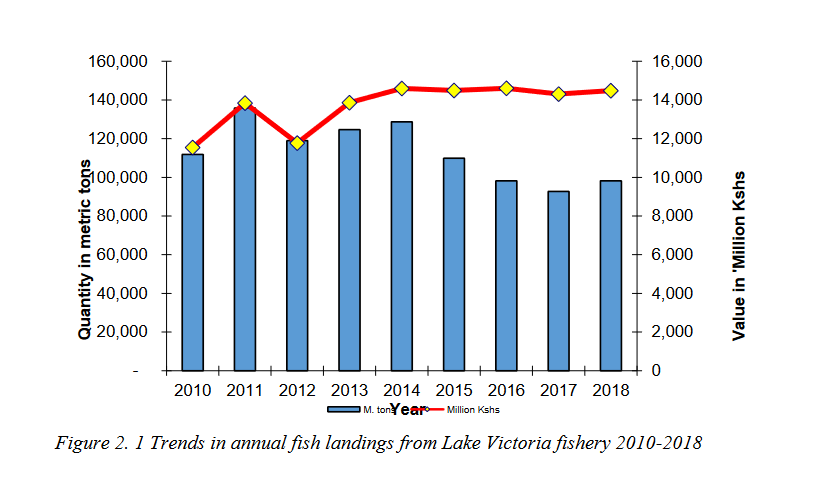

KEMFRI notes that despite more than 60 percent of fish production in Kenya and one percent of captured fish globally comes from Lake Victoria, fish production in the lake has declined from 200,000 tons in 2002 to 98,000 tons in 2022.

“There is fishing pressure, water quality changes, unbalanced predator-prey relationship, and governance issues which have to be checked,” said Dr Christopher Aura, the Director of Fresh Water Systems Research at KEMFRI.

A journal published by ScienceDirect in April 2023, and titled ‘Response of fish stocks in Lake Victoria to enforcement of the ban on illegal fishing: Are there lessons for management?’ pointed out notable reductions in some aspects of fishing effort in the lake since 2016.

According to the journal, a fishing effort survey conducted in December 2020 indicated that the total number of fishers decreased by 4.2 per cent, from about 220,000 in 2016 to 210,600 in 2020.

“During the same period, the number of fishing boats decreased by two per cent; monofilament nets decreased by 35.5 per cent; and beach/boat seines decreased by about 35 per cent,” quoted the journal.

The graph below is extracted from Fisheries Annual Statistical Bulletin 2018, published by the State Department for Fisheries and the Blue Economy in 2021

And five years ago, Opondo could not bear anymore the pain of having overnight ventures into the lake and coming out empty handed.

Homestead Food Security Model

One day, while taking care of his livestock in a nearby grazing field, Opondo noticed a compound full of fruit trees and crops.

The owner of the home was a person well-known to him, Mr Michael Nyaguti.

e felt we needed a local solution in which every fisherman would understand issues around conservation so that we could save the lake

Michael Nyaguti

“I interacted with him for some period, and he told me what I had witnessed was as a result of a project he was part of,” said Opondo.

The project titled ‘Homestead Food Security Model’ was aimed at providing alternative livelihoods to the fisher folk in the area following the dwindling fish stocks.

“I was raised from the fishing resources, and that is what everyone in this village depends on,” said Nyaguti.

As opposed to many other fishermen, Nyaguti did not just frown at the dwindling fish stocks, but reached out to colleagues to find a solution to the problem.

When you tell the fishermen not to catch the small fish, yet the big fish is not available, they do not see any sense in it as they are in dilemma of leaving the small fish for posterity and having their families have nothing to eat

Michael Nyaguti

And in 2009, they founded Magnam Environmental Network, which championed for conservation of the lake to ensure sustainability of its resources.

“By this time I was a chair of the area Beach Management Unit, and a number of us thought that there was a big problem with the enforcement of government regulations on fishing,” said Nyaguti.

“We felt we needed a local solution in which every fisherman would understand issues around conservation so that we could save the lake,” he added.

This involved self-regulation, especially in line with the eradication of illegal fishing gears, sustainable utilization of the lake resources, and general environmental conservation of the lake.

“Use of illegal fishing gears was rampant as fishermen wanted to maximise on their catch, and in the process catching small fishes, which needs to grow to maturity and reproduce,” he said.

But one of the biggest challenges in convincing the fishermen to adhere to the fishing regulations was the need to feed their families.

“When you tell the fishermen not to catch the small fish, yet the big fish is not available, they do not see any sense in it as they are in dilemma of leaving the small fish for posterity and having their families have nothing to eat,” said Nyaguti.

It was then that the network introduced ‘Homestead Food Security Model’ which saw fishermen engage in farming within their compounds so as to provide alternative source of livelihoods.

“With this kind of produce, a fisherman can take a break from fishing, but still be sure to put food on the table. The fishermen can also avoid catching small fishes, and this contributes to reducing fishing pressure,” said Nyaguti.

At his home, Nyaguti’s house is surrounded by sugarcane, bananas, vegetables, and a number of fruit trees.

He has spread the planting season to ensure that he sustains the supply.

To maximise his income, Nyaguti is providing value addition by making sugarcane juice which he sells at the nearby Otonglo market.

“My home is now a demo farm, and lots of people come here to take seedlings and learn how to do the home farming,” he said.

“Many homesteads have a lot of idle spaces, and our idea was to utilize these spaces to produce food. Having your farm in the compound also boost security of the produce as you are close to the farm,” he said.

“Having your farm in the home also gives you the urge to work hard and care for the farm as you see your crops every time, as opposed to farms which are far away from homes and you only visit once in a while,” he added.

Widows and the dwindling fish stocks

About one kilometre away from here is the home of Syprose Achieng who has also embraced this model.

Achieng’s family had depended on fishing for several years till the death of her husband in 2001.

“By the time my husband died, the fish catch was already going down and I used to supplement his income with my cereal business,” she said.

With the husband no more, Achieng tried out the business of selling fish, but this did not go well due to the low catches.

By the time my husband died, the fish catch was already going down and I used to supplement his income with my cereal business

Syprose Achieng

She embraced the home farming model, and now her home is covered in sugarcane, pawpaw, bananas, potatoes, and various fruit trees.

“Since I began this project, I stopped bothering myself with the fish business,” she said, adding that the income from the project, supplemented with the cereal business is able to cover her domestic expenses, as well as pay school fees for her children.

Her story is not different from that of 90-year-old Mama Wilfrida Owiti whose home is about 700 metres away.

During her heydays, she helped her husband with fishing activities.

“The man would venture into the lake, and when he came back he would be having loads of fish. I would help him with offloading the fish from the boat, and selling,” she said.

“There was a lot of fish those days. You could just have a walk at the beach and fishermen would give you fish for free,” she added.

When she lost her husband, the supply of fish dried up, and she had to depend on other fishermen to sell her fish before she goes to the market to resell.

But with time, the demand for fish went up while the stocks reduced, forcing her out of the business.

She joined the home farming project in 2016, ad ventured into vegetable farming.

“Today, I pinch a few leaves of my kales and go to the beach. People buying fish also buy my vegetables. Other people come home, while others buy wen I go to the market,” she said.

Despite the project gaining traction in the area, Mr Nyaguti notes that erratic weather caused by climate change has been one of the major challenges.

“When there is no rain, we have to go all the way to the lake to get water to irrigate the farms. We are also experiencing occasional disease outbreaks in our farms,” he said.

He calls upon the county and national government to invest in the project by providing water infrastructure and extension services so as to have more people onboard.

Another major challenge is that a number of people in the area are selling off their lands, hence reducing the area available for tilling.