Two years ago, Jacob Olwanda wished his daughter death. He could not cope with the derogative ridicule from friends and foes over the health of his daughter.

Despite Olwanda looking physically healthy, strong, and lively, his daughter’s case was a sharp contrast to him.

“She had lost so much weight, which made our family a laughing stock in the village. Some people mocked me that I was consuming everything and leaving children hungry,” said the father of five.

‘We suspected witchcraft and tried to seek help from all corners to no avail. I made more enemies than friends, but I am glad I am gradually reconciling with them’-jacob olwanda

At three years of age, the daughter weighed nine kilos, against the recommended weight of between 12 and 18 kilos for an average child of this age. The situation even made Olwanda avoid hospital visits due to stigma and resort to interventions through traditional medication.

“We suspected witchcraft and tried to seek help from all corners to no avail. I made more enemies than friends, but I am glad I am gradually reconciling with them,” he added.

It was not until June 2024 that Mr Olwanda discovered that his daughter was suffering from severe malnutrition.

What is malnutrition?

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), malnutrition refers to deficiencies or excesses in nutrient intake, imbalances of essential nutrients, or impaired nutrient utilization.

This condition, caused by a combination of poor-quality diets and poor health environments, may take the form of undernutrition, overweight, and obesity. WHO says undernutrition manifests in four broad forms: wasting, stunting, underweight, and micronutrient deficiencies.

A child who is underweight (low weight-for-age) may be stunted (low height-for-age), wasted (severe weight loss), or both.

Wasting occurs when a person does not have adequate food or has had frequent or prolonged illnesses. It is associated with a higher risk of death in children if not treated properly. At the same time, stunting is a result of chronic or recurrent undernutrition, usually associated with poverty, poor maternal health, and nutrition, frequent illness, or inappropriate feeding and care in early life. It prevents children from reaching their physical and cognitive potential.

According to WHO, in 2022, 149 million children under five globally were stunted, while 45 million were wasted, and 37 million were overweight.

Malnutrition screening in Kakamega

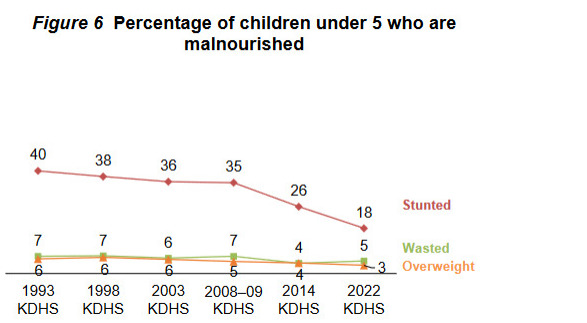

On the other hand, the Kenya Demographic Health Survey (KDHS) 2022 reported that 18 percent of children were stunted, 11 percent were underweight, and five percent experienced wasting.

KDHS is a survey that collects health and demographic data, including nutrition, at the national, rural, and urban levels. The Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) survey is conducted in collaboration with the Ministry of Health and other stakeholders.

The same report showed that only 22.9 percent of children in Kakamega County accessed minimum acceptable diet, with 12 percent of children being stunted and 6.4 percent wasted.

‘Today, I look at my daughters and am proud of them. I am also in the process of reconciling with people I accused of ruining the health of my daughters’-jacob olwanda

When Lake Region Bulletin caught up with Mr Olwanda at his Alumako A village in Musanda, Mumias West in mid-November 2024, he could afford a smile. The daughter was on the road to recovery.

“Today, I look at my daughters and am proud of them. I am also in the process of reconciling with people I accused of ruining the health of my daughters,” said Olwanda.

Usaid Boresha Jamii Project

Olwanda’s two children are part of a nutritional intervention program, Usaid Boreja Jamii (UBJ), by the Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology (JOOUST) and the Kakamega County Government, through funding from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

According to the project initiators, routine growth monitoring and promotion in the county in 2022 revealed that 992 children under five years were identified with faltering growth, with over 40 percent of the cases traced to Olwanda’s home area of Musanda Ward.

“Another round of the open day was conducted in which a total of 506 children were assessed; among these, 129 had moderate malnutrition showing yellow Mid Upper Arm Circumference measurement (MUAC), and 25 had Red MUAC,” said Dr. Elizabeth Omondi, Team Lead for Reproductive Health, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health, Nutrition and Water, Sanitation and Hygiene-WASH (RHMNCAH/Nutrition/Wash), and a Lecturer at JOOUST.

This revelation prompted the County and USAID Boresha Jamii project to support the Ward in improving the situation through community-led approaches, such as the Baby Friendly Community Initiative (BFCI) and Positive Deviance Hearth.

While BFCI protects, promotes, and supports breastfeeding, optimal complementary feeding, and maternal nutrition, Positive Deviance (PD) is a behavioral and social change approach to managing malnutrition.

“Positive deviance heart is a globally proven model in enhancing the capacity of communities to successfully treat and rehabilitate the malnourished children within the community set-up,” said Dr Omondi.

She added: “With global pandemics on the rise, high levels of hunger and poverty, cases of malnutrition (underweights, stunting and wasting) affecting children below five years are on the rise, hence need to enhance the capacity of communities in rehabilitating the malnourished and those at risk.”

Kakamega’s Sh16 menu

Through the PD health project, 20 Community Health Volunteers (CHPs) from two Community Units (CUs) were trained on these concepts. Two Community Health Assistants supervising each of the CUs and an area Public Health Officer were also trained.

The team managed to identify 154 children from 120 households who were eligible for the program.

“The guiding principles of PD/Hearth are quick results, culturally acceptable, home-grown solutions, use of locally available and low-cost nutritious foods, community participation/involvement, economical and sustainable,” said Rachel Kavithe, UBJ Nutrition Coordinator.

Ms. Kavithe added, “Malnutrition affects children from rich and poor households. This might also be associated with caring, hygienic practices, and other food availability. The programs aim to share knowledge and skills on the feeding and caring of infants and children in households within the same set-up.”

According to Ms Kavithe, the nutrients required in a meal include 600 to 800 calories, 25 to 27g of Protein, 300 μg RAE (RAE = retinol activity equivalent) of Vitamin A, 8 to 10mg of Iron, 3 to 5mg of Zinc, and 15–25mg of Vitamin C.

The menu components included grains, eggs, nuts and seeds, meat, fish, leafy vegetables, vitamin A-rich vegetables, and fruits.

In Musanda, Ms Kavithe noted that maize flour, rice, eggs, groundnuts, omena, pumpkin leaves, carrots, oranges, tomatoes, and onions were recommended after a market survey showed that this menu was affordable to many families. Depending on the choice of the components, this medicinal meal would cost as low as Sh16 for a single child.

One is good to go with just five spoons of maize flour, five pieces of omena, two pumpkin leaves, a carrot or pumpkin, and a pinch of salt. This would be supplemented with a healthy snack, such as a banana, avocado, or orange.

An alternative menu included rice, an egg, pumpkin leaves, tomatoes, onions, groundnuts, and a pinch of salt.

“Some considerations include whether the menu contains the correct protein, calorie, and micronutrient composition. Is the food quantity (volume) in the proposed menu a realistic amount for a child to eat? Does the menu include locally available and accessible foods? Does the menu include a snack? Is the cost per serving realistic for an impoverished family?” noted Kavithe.

“Remember that a child’s stomach is no larger than the child’s fist,” she added.

Once the ingredients are ready, one chooses the method of preparing the food, considering the preservation of nutrients and the type of food.

After cleaning, the food is mixed together to form a nutrient-rich meal. Examples include rice, green vegetables, eggs (either boiled or sometimes fried with vegetables), peanuts or peanut powder, carrots, and tomatoes.

Mostly, the food is fried with moderate oil to provide energy and allow the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins such as Vitamins A, D, E, and K.

Peanuts are roasted and eaten or powdered after roasting to enrich the snack or leading food.

During feeding, hand washing and all hygiene aspects are carefully observed. Caregiving practices are also observed by ensuring responsive feeding, which allows good interaction between caregiver and child.

After religiously adhering to this menu for three months, Olwanda’s daughter’s weight jumped from nine to 11 kilos.

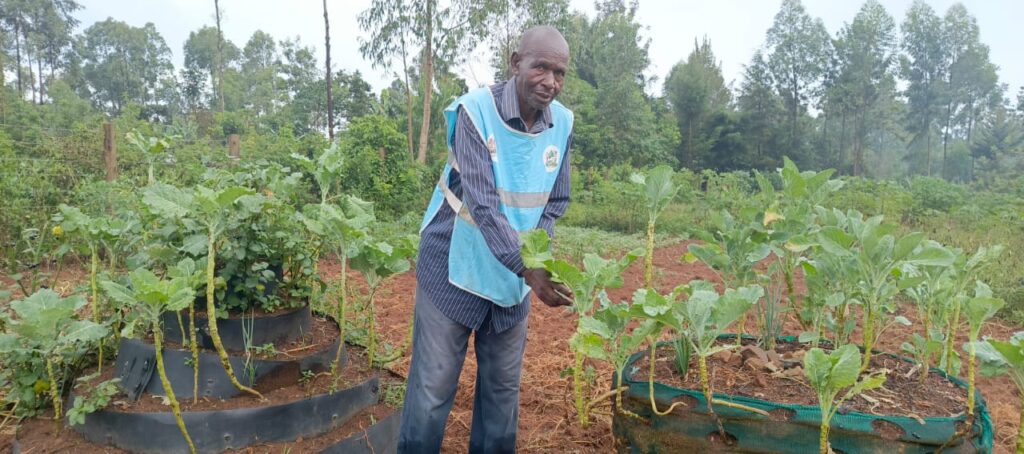

“Today, I have my kitchen garden with crops all the time. I do not look far since I discovered that the solution to my daughters’ problems is within my compound,” he said.

Since most of the menu components are grown locally in the area, to achieve sustainability, project beneficiary households were inducted into setting up kitchen gardens where they could grow food crops providing the vital nutrients required.

Mother to mother support groups

It’s a calm afternoon at Halomba Village in Mumias West, and 66-year-old Millicent Bati is preparing a delicacy.

Ms Bati is a beneficiary of the project following the enrolment of her three-year-old granddaughter.

Just like Olwanda, Ms Bati faced discrimination over the health of her granddaughter.

“The baby was pale and sickly. Some neighbors prevented their kids from interacting with her, and I felt so low,” said Bati.

She added: “Whenever I was going out of the compound with her, I would ensure I covered her well so that no one would see her.”

However, when she joined the program, she became an active member. Her home was used for demo sessions for the members of the 14 households in this Community unit.

“In the sessions, each member carried small portions of the recommended food items, which we prepared and fed to the children. It has worked wonders,” she said.

Today, she has a kitchen garden on an eighth-acre parcel beside her house.

“This project has opened my eyes to the reality that we have solutions within us, and it is lack of knowledge that makes us wander around looking for imaginary help,” Ms Bati said.

“My once weak and timid granddaughter has gained weight, gained confidence, and I am enrolling her in school next year,” she added.

A quarter-acre parcel of land at Musanda Dispensary is used as a demo farm. The facility donated the space to help residents learn the concept of a kitchen garden and provide them with seedlings.

Dickson Wanangwe, a Community Health Promoter in this village, was one of those trained in the UBJ project and participated in implementing the PD hearth.

“One of the biggest challenges we discovered was that some families could not afford seedlings. Therefore, this farm helped us nurture seedlings, which we gave to those lacking,” he said.

He says the project improved his understanding of malnutrition, and he has since become a champion for the kitchen garden.

“We are currently trying to get more men involved since they are key decision-makers in a family. Hence, their support will likely greatly impact the fight against malnutrition,” he said.

Wanagwe’s sentiments are echoed by Musanda Dispensary Incharge, Josephat Nyongesa who added that the facility has since embeded nutritional education as part of their maternal and child health.

“Now all our clinic visits begin with capacity building of mothers on nutrition, and through the kitchen garden, help them with knowledge and skills on how to set up kitchen garded, and how to use locally available foods to enhance proper nutrition for themselves and their children. Those who can’t afford seedlings get them from the garden,” he said.

Mr Nyongesa noted that the facility is gradually relieving itself from the burden of dealing with malnutrition cases.

“We are glad that 15 CHPs attached to our facility benefited from the training, and they are now championing for proper nutrition in the communities, working with mother to mother support groups. This has saved us the many referrals we used to receive on such cases,” he added. “We have also seen an increase in immunization.”

Porridge alone is not enough

Caren Akinyi, Mumias West Sub County Health Promotion Officer said that since Kakamega has appropriate agricultural land and a climate that supports agriculture, what is lacking is the chance for social behavior to utilize this opportunity in the fight against malnutrition.

“Having engaged the residents, you realize that they have the food, but they do not know that this food they are having can make their children have good health,” said Akinyi.

“For example, these people plant groundnuts but do not use them to enrich their children’s food. So in the PD/Hearth, we are ensuring that every meal has groundnuts to provide the desired proteins in the diet,” she added.

She noted that many mothers in Kakamega believe in giving their children carbohydrate-laden porridge, which limits the children’s nutritional supply.

“So with this program, we are telling the mothers that if their children above six months old can eat, they need this menu,” she said. “The PD/Hearth had four key components: feeding, caring, hygiene, and health-seeking practices.

She said the program also helped the County Government identify children who had defaulted on immunization and those with underlying conditions for appropriate referrals.

UBJ breakthrough

According to Ms Kavithe, 90 percent of the 129 children with moderate malnutrition who enrolled in the program achieved the targeted weight gain.

She noted that the Ministry of Agriculture also supported all caregivers in establishing home gardens and keeping small animals.

“One of the greatest lessons learned in this program is that the solution to malnutrition lies within the community. They only need to be empowered with knowledge, and nutrition multisectoral engagement plays a major role in malnutrition reduction,” said Kavithe.

To entrench this concept in the communities, Ms. Kavithe said there are plans to include the program in the County Annual work plan and County Integrated Development Plans (CIDP), and scale-up will be done to areas identified with high malnutrition through routine nutrition screening and household visits by CHPs.

‘One of the greatest lessons learned in this program is that the solution to malnutrition lies within the community. They only need to be empowered with knowledge, and nutrition multisectoral engagement plays a major role in malnutrition reduction’-Rachel Kavithe, UBJ Nutrition Coordinator

“This initiative takes a multisectoral, multi-actor approach. The Ministry of Agriculture is at the frontline to guide the establishment of home gardens. At the same time, the Social Protection Department identifies very vulnerable children for inclusion in any available national safety net programs. Local leaders, community nutrition champions, grandmothers and fathers as opinion leaders continually communicate nutrition messages in community forums,” said Kavithe.

Despite the success of the project, affordability of the medicinal meal may pose a challenge in urban areas where there are limited or no spaces setting up kitchen garden, as well as dry areas where it may be expensive to manage such a garden.

Ms Akinyi also notes that changing community attitude on nutrition may also pose a great challenge, as entreched nutritional behaviour may require long time to change.